Obviously he was a noted automotive writer. As discussed previously, he inaugurated the idea of testing for cars. He sold the idea to Mechanix Illustrated, which was a Fawcett Publications periodical, from the 1940’s to the early 1970’s. Interesting to notice that the Magazine refused to acknowledge his death and kept his column as Tom McCahill Reports that was ghostwritten by his stepson Brooks Brender. We will use a lot of the material he left at Mechanix Illustrated.

Besides Mechanix Illustrated, Tom McCahill also wrote for True, also known as “True, The Man’s Magazine”, was published from 1937 to 1974 by Fawcett Publications. During the 1950s, famous automotive author Ken Purdy was its editor.)

He also published:

- Tom McCahill on Sports Car, Fawcett Publications, Inc Greenwichs, Connecticut, 1951

- The Modern Sports Car Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1954.

- Tom McCahill, Today’s Sports and Competition Cars, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1954.

- Tom McCahill, Tom McCahill’s Car Owner Handbook, Arco Publishing Co., New York, 1956.

- Tom McCahill, What You Should Know About Cars,Fawcett Crest Books, Circa 1963.[6]

I have fortunately managed to get all these books an I had a lot of fun reading them. It is not practical, and not necessary to transfer all the contents of his books to the Internet, not to mention that this might incur breaking some copy rights. To prevent this I will limit the use, although more than 60 years already passed, and there should be no contention about. Probably, sometime in the future, somebody will think of publishing all of them as it has been done with Mechanix Illustrated old issues. I should mention that this whole exercise is void of money oriented aims, my idea is to honor Uncle Tom McCahill, give him the credit he deserves for inventing the car reviewing business, save it for posterity and, maybe above all, have fun!

A word on his “complete works”

It can fairly be split in three groups: Books, Handbooks and Car Testing, mostly at Mechanix Illustrated.

Books

Books, as such, he only wrote two, both in 1954, i.e., The Modern Sports Car and Today’s Sports and Competition Cars, both from Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. The first is dedicated to Joe, his Labrador retriever, who died (he says killed) in an accident and the other book he dedicates to the IRS. Both are concerned with sports car, be it for competition or simply fun. These books are different enough to insure the image Uncle Tom have of complete honesty to the reading public, and not a lesser act because he was held down by the IRS. But they somehow are redundant to this first handbook, Tom McCahill on Sports Car, Fawcett Publications, Inc Greenwichs, Connecticut, 1951. Since I will cover this handbook extensively more than any other publication, I will extract from the two books the following chapters, and the dedicatory, which will top my review on his first publication:

From The Modern Sports Car: Dedication and It All Boils Down to this.

From Today’s Sports and Competition Cars: Dedication and What It’s All About.

Dedication I

To JOE, my Labrador retriever, who was killed in an acci-

dent.

For almost six years he was my constant companion on

every automobile test I made. He sat by my desk as this book

was written, always hoping I would stop and take him hunt-

ing. Joe was the official mascot of the American Sports Car

Team in Europe in 1952 and 1953, and was also a duly elected

member of the Yale University Sports Car Club.

Joe was one of the greatest gun dogs of all time, and in six

hunting seasons, in all parts of the world, he never missed a

single retrieve.

He was a real sports car fan and loved high speed driving.

Anyone who came to my house in a sports car was always wel-

come, especially if it had a deep exhaust roar. Extra nice

Detroit owners were tolerated.

He was a great guy.

Dedication II

To the Internal Revenue Service.

Without their constant prodding

and urging, this book would

never have been written. If

enough copies are sold, perhaps

they’ll leave me a crumb or two

It All Boils Down to this

By now, if you have read all the mumbo-jumbo that has gone before, you must realize sports car people are just a few notches different than the dyed-in-the-wool, conventional mugwump.

In a sentence or even less, a word, it all boils down to one simple fact-sports car people have the “feel.” Maybe it’s an appreciation for the better things of life, or a normal revolt against regimentation on a commercial scale.

One thing is certain, the true sports car man revolts against taking to the highways like a duck parading with millions of other ducks in vulgar creations created to catch the eye of vulgar people. As this book is being put to bed, the writer has noticed an increase of idiotic Sunday newspaper supplement articles slanted to soothe the Detroit ad buyers by condemning all types of sports cars and sports car owners. These are generally written by intellectual delinquents with no mechanical, and very little family, background. These Union Square soap-box editorialists usually have the literary talent of a Borneo gorilla and usually only succeed, I am glad to say, in interesting more people in sports cars.

Unless you have the “feel,” sports cars definitely are not for you. The man who doesn’t feel that his MG, Austin-Healey, or Jaguar is a sporting and adventure companion just doesn’t have it. I realize many sports cars are bought primarily for show-off purposes, but this is only a small part of what the sports car man knows about the sport.

Let’s take a hypothetical trip in a sports car, all alone. Actually, although you never tell this to your wife, sports car driving on a trip is more fun alone. You don’t need your wife or close friend to keep you company-your sports car is your good companion. It is impossible to get this feeling with a cold, Detroit commercial stamping. Let’s say your car is a little Austin-Healey. Everything about it is top quality of the very finest material. Unlike your Cadillac, Lincoln, or Chrysler, you have a feeling for this little car, an affectionate regard almost like one you have for that good dog you own. When on the highway, you often talk to the little car as if it had warm blood running through its veins. Well, it is a friend, and warm liquid is running through its veins, though in this case it doesn’t happen to be blood.

After the car has given you exceptional pleasure on a fast 100 or 200 mile jog, which may have been a business trip or to another friend’s for a weekend, you often, as you get out, give the fender a friendly pat of thanks. (How long since you’ve patted a Cadillac?) The man who does this has the “feel.” He may never race, enter a hill climb or a rally, but he has the “feel.” Let’s say you work in New York and live in New York, and garage your little jewel in a not-too-tidy auto hotel where it is continually surrounded by unaesthetic iron. You find yourself often just before you turn out the lights at night wondering how they’re treating your pal over in the garage and whether dirty hands have been marring its highly polished finish. Our hypothetical trip, and it actually happens every day to thousands, starts in your office. Old Joe Blow, the firm’s wealthiest client, wants you to come down to his plantation near New Iberia in Louisiana for some late fall duck shooting and the possible discussion of future plans.

Your secretary checks the air schedule and trains. By plane, it’s just an afternoon’s hop, but you elect to do something that has the other men in the office slightly suspecting your sanity when you announce that you’re going to drive down in your Austin-Healey. You don’t get mad at the many questions, such as, “Supposin’ it rains, can you keep dry in that bucket?” or remarks that it would be a lot safer and cheaper to fly. You don’t try and explain-these fellows have all the adventure in their souls of a meek ribbon clerk and couldn’t understand if you told them. So you just say goodbye when the time comes and leave the office ignoring a wisecrack or two about walking back or hitch-hiking.

It is exactly four A.M. when your alarm clock lets go like a furious rattlesnake and, with high adventure ahead, you’re out of bed and wide awake in the first jump. Twenty minutes later the sleepy night elevator man in your apartment building eyes you suspiciously as he takes your gun case, duffel, and kit bag. You leave these in the lobby and make the two block risk walk to the garage. The night garage man openly looks at you with suspicion as he shufflingly leads you over to junior, parked way in the back between two man-made mountains of chrome. You give it a fond pat on its left flank and slip behind the wheel.

The top is up and the passenger side curtain is on. With the adequate heater and your big greatcoat you won’t need the other side curtain as the temperature outside is a mild 40 degrees. You turn the key and instantly the engine roars awake.

You let it idle for several minutes and then pull up to the gas pumps. The tank :filled, you drive back to your apartment for the bags and your gun and, with these in place in the trunk, you head for the Jersey Turnpike.

The speed limit is 60 MPH and in overdrive the engine is happily loafing at 70, a speed you calculate will not attract John Law. You are just settling down to the trip when a turnpike all-night restaurant-service-station looms, reminding you you haven’t even had your coffee. After a good, solid breakfast (the driver on a long trip needs plenty of fuel just as the car does), you emerge from the diner and find that it’s just daylight.

Now you’re really on your way at your steady 70. The car wants to go faster, but you hold off, the cops are thick on this throughway (in more ways than one). As the sun comes up over your left shoulder, signs indicate Philadelphia somewhere on your right.

The engine is purring a song that no symphony could compare to. As they say in the Ozarks, boy, you’re really livin’it up! – and you know it. Ever since you pulled out of the tunnel back in New York there’s been a tingle in your spine, areal,perpetual, underplaying thrill that seems continuous. In a short time you’re over the Delaware Memorial Bridge, a short shot through Delaware into Maryland and onto the great Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

As you cross the bridge you slow down, noticing several Hocks of canvasbacks trading back and forth. The fact that you’re going all the way to Louisiana for duck shooting momentarily strikes you as a little silly when right now you are over some of the greatest duck shooting water in the world. Around Annapolis and over to U.S. 301, and then the high Potomac Bridge and more ducks. Now you are in Virginia. At Port Royal you pull up for a second breakfast and re-fueling.

It’s only a quarter of eleven, the day’s young. A fast trip through the City of Richmond, and then a s-l-o-w drag through Colonial Heights and Petersburg. Once clear of Petersburg you snap back to life quickly and head for South Hill and Raleigh. At three o’clock you’re not even tired, though you’ve been driving ten hours, at moderate speeds for the Healey-which made the trip effortless. In Raleigh you get yourself a late, late lunch or an early dinner and head for Southern Pines on U.S. 1, 70 miles further south. In the outskirts of Southern Pines you find a beautiful motel with a restaurant and a vacancy, so you pull in. It is five o’clock and you’ve covered just under 600 miles.

The year before when you made this same trip in your Detroit car you were pooped, but tonight after a quick shower and shave (so you won’t have to do it in the morning) you feel like a million dollars.

Of course you had to answer with a smile several times in the restaurant when the motel manager and one or two other friendly people asked, aghast, “You mean to say you came all the way from New York in that little thing today?” Then they’ll usually add, “Why, that would even be a long trip for my big Buick [or DeSoto].”

You smile back friendly enough, but don’t try and explain. Ignorance knows no limitations and your mission in life is not the education of the multitude.

Happily, you find the motel coffee shop open at six the next morning. After a big breakfast of flapjacks and grits, you’re on your way once again, bowling down U.S. l. On the way back you’ll come by way of Atlanta and the Piedmont Trail, but this time you’ll stay on U.S. 1 until just south of Augusta where you head west for Macon and Montgomery. Down to Mobile and along the Gulf on #90 to New Orleans. Then the short run to the plantation on Vermilion Bay where the mallards come up like thunder just at the break of day. By nine o’clock you’ve taken the passenger side curtain out, and by ten, when you stop for a second breakfast and re-fueling, down comes the top itself. It’s late November, but the temperature is in the high sixties. Just after eleven o’clock you make the swing west a few miles south of Augusta. The deeper you penetrate the South, the more attention your car gets, especially from the children on the roads, who wave and yell gleefully as you pass.

That afternoon, after leaving Montgomery, you head south toward the Gulf and at night you pull into another motel near Mobile. At noon next day you are in New Orleans and stop off to see your old friends at La Louisianne, that fabulous restaurant, for a meal that no king has been able to buy for some time.

By mid-afternoon your little gem, tooling along under the moss-laden trees, sounds just as solid as when you left the garage many miles back. You are now driving in your shirt sleeves and are feeling pretty smug about yourself and life in general since you’ve just blown off a couple of Louisiana hotrodders with ease. As you pull up to the plantation you give the instrument board an extra-friendly pat for a job well done-but your host won’t let you leave the car. He has to feel the seats, kick the tires and touch the paint, then the old routine again, “You came all the way from New York down here in that?” By now you’re feeling so good about everything, so superior to most of your fellow earth-dwellers, you almost tell Old Joe Blow to go climb a tree – in fact, you do, but you’re smiling. Three days of wonderful duck shooting and another big order from Joe and you’re on your way home. You find as you are tooling over the highway some of the roads in the south are long, fast and deserted. You pass 100 MPH on several occasions and cruise at 80 or 85 much of the time. You’re all alone, and you sing to yourself as you haven’t sung in years, and whistle off-key as much as you please; the car doesn’t protest,

and you never have to slow for a corner but just keep bowling along.

Old Betsy, your prize-double barrel gun, did you proud, and you suddenly realize that the deep affection you have for this gun that was given to you before you entered college is similar to the feeling you have for this car. Both fine pieces of sporting equipment and both good companions. You understand this, you have the “feel.” Those realists can have their reality, this is for you. A man’s gun and a man’s car. As you unload in front of the apartment you realize a great adventure-nothing really much, no lions, no tigers, no rescues at sea – but a great adventure you and your friend, the car, a sports car, have had together.

If you have it, you’ll know what I mean. If you haven’t, it’s just too damm bad

Tom McCahill On Sports Cars

Let’s Start with Sports Cars, the first on the left above. Better yet, let’s not forget the staff behind, probably already gone, by with my thanks and to the best of my knowledge, without breaking any copyrights, since I will limit the use and more than 60 years already passed. Perhaps, sometime in the future, when the subject is exhausted I will think of publishing it as it has been done with Mechanix Illustrated old issues.

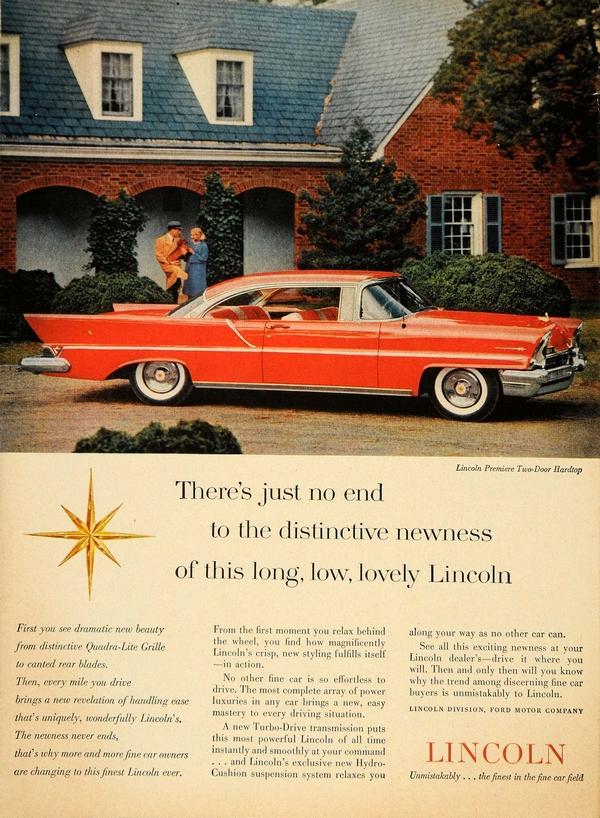

Since nostalgia is a high point in this site, let’s get started with two propaganda adds:

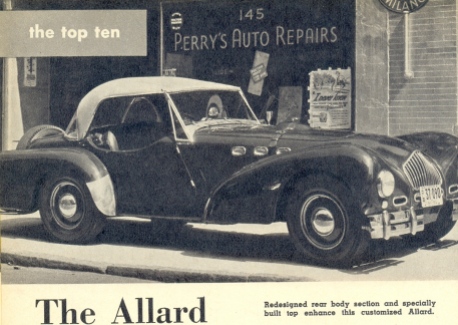

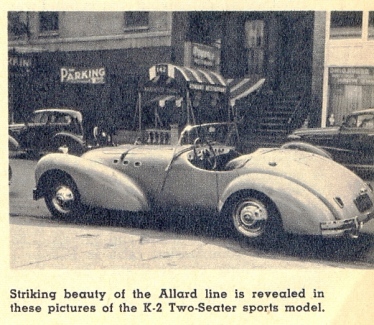

Let’s take a look in the contents separately: